Unlike Acconci who used the streets of New York, or Burden who enlisted such props as a rifle and a Volkswagen Bug, Walther eschewed materials and scenarios connected to the day-to-day environment. His abstract, geometric cloth sculpture, photographed under the artist’s direction out-of-doors in the natural but featureless setting of a grass-covered field, conjured a timeless, abstract world in which one could imagine a connection to ancient ritual or even the non-referential strategies of neo-plasticism and minimalism. And all his work seemed surprisingly connected to strategies appearing during the same years in the work of the choreographers of New York’sJudson Memorial Church group, especially Yvonne Rainer, whose work in dance also brought to the foreground everyday movement.

As with Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty or Burden’s various performances of the era, it was really only possible to know Walther’s work through the highly stylized photographic documentation that the artist himself produced. My perceptions of Walther’s work were thus structured around the photos and the powerful interpretation that the photos added to the performances. The stark, featureless flat fields of grass or hay that Walther chose as his setting convey a mythic otherworldliness reminiscent of the metaphysical landscapes in the contemporaneous movies of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni. In many of the pictures, the performers are photographed from above with the help of a tall ladder or scaffold, assigning to the viewer, as well as the photographer, a magisterial aerial point of view on the action below. Walther’s use of high contrast black-and-white gives these photos an anti-sensual austerity and existential grit as well.

My second encounter with the work of Franz Erhard Walther took place in the ’90s, when I was asked to write a catalogue essay for a museum exhibition of the artist’s work [“Franz Erhard Walther – Work Needs the Body: A Strong Misreading” in Franz Erhard Walther – Ich bin die Skulptur, Kunstverein Hannover, Germany, 1998]. Re-examining the work, or rather the photos of the work, it seemed to me reflective of the ideas of Michel Foucault about the regulation and control — what Foucault called the discipline — of bodies. It was Walther’s sculptural expression of this regulation of bodies that impressed me. The power of the work, I wrote, “comes from the fact that he does not simply picture or describe bodies in this regulated geometric space. Rather he asks himself and others to themselves experience this space, like pilgrims retracing the Stations of the Cross.” I viewed Walther’s human actors as subjected to the author’s rigid control of space, as denied any vestiges of their individuality, as mere cogs in the construction of an abstract geometric order fashioned “of only two materials, the warm living body and the soft limp cloth.” I saw the very non-referential quality of Walther’s pieces as intensifying this Foucaldian narrative. Here, the discipline of bodies served no practical worldly goal — the performers were solely enacting a purified aesthetic of controlled bodies in space.

I was well aware that, with this interpretation, I was articulating a “strong misreading” — to use Harold Bloom’s term — of Walther’s work, substituting a focus on power relationships for the artist’s own stated emphasis on phenomenological experiment, the primacy of materials, and the making of community as the guiding themes in his work. And yet the performances, as seen in the photographs, seemed to demand this recoding of the work. After Foucault, it was impossible to accept the neutrality or objectivity of the formal and phenomenological investigations of minimalism or conceptualism. After Roland Barthes, it was impossible to say that a work of art had a single signified, determined by its author. Rather the work became open to myriad, successive signifieds, actively created by its readers or viewers.

And then there is my third encounter, in which, after so many years, I finally came across the pieces from Walther’s “Werksatz” series in all their three-dimensional majesty and complexity when they were exhibited at Dia:Beacon this past October. In a large room within Dia’s sprawling building, the fifty-eight cloth “Werksatz” pieces, all elegantly folded, ready for travel or use, were arrayed on low benches around the walls. On the floor was an industrial gray carpet, covering almost the entire room, leaving only a narrow walkway on all four sides. Guided by an unobtrusive docent, visitors were invited to try out the pieces one at a time. Each individual, pair or group of people out on the carpet interacting with one of the pieces instantly became a performer, observed by the remaining visitors scattered around the edges of the room.

That day, almost forty years after first seeing the photographs, the work itself spread out in all the richness of its materiality and temporality, transcending and defying ideological reading, providing instead waves of complex experience.

With a partner, we performed two of the most well known pieces, Sehkanal (1968) and Körpergewicht (1969). The photos had indicated nothing about the intricacy of the experience, of the slowness of unfolding the tightly bundled pieces on the floor, or, at the end, refolding them again along their prescribed crease lines to reassume their origami-like shapes. The photos said nothing about the beauty of the pieces themselves, exquisitely stitched and constructed with couturier skill out of delicately colored cloth. Nor had the photos conveyed the physical creativity required to attain the balance and tension necessary to make the pieces come to life, the awkward shifting needed to permit two opposing bodies to attain equilibrium. Watching other people perform, one saw untrained individuals instantly transformed into expressive dancers. It was all beyond the limits of photography, beyond the capacities of any kind of documentation.

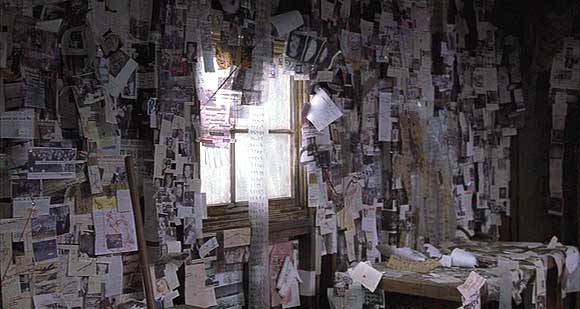

This tale of interpretation stops here for now. What a long strange trip it’s been. It is a tale of Walther’s work, its photography, and its exhibition, and a tale of my own churning subjectivity. Was it futile to read Walther’s photographs of the “Werksatz” series as capable of conveying so definite a meaning? Despite their stylistic consistency and power, were they only documentation? Would it be equally inadvisable to analyze a painting based on a photographic reproduction? But that is done all the time. Did the artist really intend two shadings of meaning in his sculptural pieces and in his photographs of those pieces? Or did the medium dictate Walther’s message? Here, the writer stops, lost in the hall of mirrors, finding himself turned round in a kaleidoscopic world of reading, misreading and rereading.

Peter Halley is an artist based in New York. In 1999 he was appointed to the Yale faculty and he is currently William Leffingwell Professor of Painting and the Director of Graduate Studies in Painting/Printmaking.

Franz Erhard Walther was born in 1939 in Fulda, Germany, where he currently lives and works. “Franz Erhard Walther: Work as Action,” is on view at Dia:Beacon, Riggio Galleries, Beacon, New York, through February 13, 2012.

|